The operating environment of an agricultural tractor is a mechanical nightmare. Heavy implement traction, uneven terrain, and continuous cyclic loading create complex misalignment, shock loads, and structural flex within linkage systems. Under these conditions, simple rigid connections often fail because they cannot relieve internal stresses, leading to fracture or deformation.

This is exactly why rod ends—and their core component, spherical plain bearings—are indispensable in agricultural machinery. They do more than just carry loads; they act as “flexible fuses” within the mechanical system.

In this article, we explore the application logic of these components across four critical tractor systems.

**Technical Terminology: Rod End vs. Spherical Plain Bearing

To fully understand the engineering choices below, we must distinguish between two terms often used interchangeably:

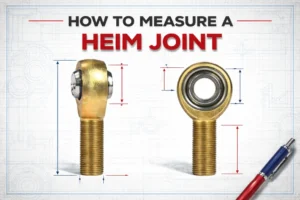

Rod End: This is an assembly. It features a housing with a male or female threaded shank (stem) enclosing a spherical bearing. Its primary advantage is ease of installation and linkage length adjustment.

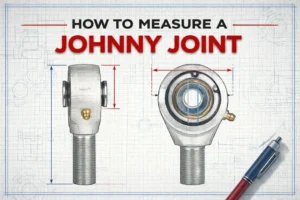

Spherical Plain Bearing (SPB): This is the core “ball and outer race” unit without a shank. In extremely high-load applications, engineers often forego the threaded rod end and press this bearing directly into a housing or cylinder clevis to avoid potential breakage at the thread root.

1. The 3-Point Hitch System

The 3-point hitch is the primary interface between the tractor and the implement. It must perform two seemingly contradictory tasks: carry immense static and dynamic loads while maintaining high adjustability and terrain-following capabilities. To achieve this, rod end technology is applied in three key areas:

Adjustable Lift Rod

The lift rod connects the hydraulic lift arm to the lower link, responsible for leveling the implement (e.g., ensuring a plow sits evenly). The adjustment mechanism is typically a threaded vertical linkage. As the lift arm moves, complex angular motion occurs between the lift rod and the lower link. A rigid pin cannot accommodate this multi-axial misalignment. Therefore, high-performance lift rods often integrate a clevis-style joint or rod end at the bottom, allowing for length adjustment while compensating for angular deviation to prevent bending.

Adjustable Stabilizer Bar

Located on the side of the lower links, stabilizer bars control the lateral sway of the implement. During operation, some freedom is needed for the implement to follow the row; during transport, the stabilizer must be locked to prevent the implement from hitting the tires. This push-pull cyclic loading requires durable connection points. Modern tractors widely use heavy-duty Rod Ends here, which withstand side impacts and allow for easy tensioning via the turnbuckle body.

Top Link

As the “third point,” the top link adjusts the implement’s pitch (angle of attack). This is the classic application for Rod Ends. Both ends of the top link must have significant misalignment angle capabilities. As the ground undulates, causing the implement to pitch forward or backward relative to the tractor, the rod end swivels like a universal joint, ensuring force is always transmitted axially. If a rigid connection were used, the moment the implement tilts, massive bending forces would snap the threaded rod.

2. Articulated Steering Systems

On high-horsepower 4WD tractors, articulated steering relies on hydraulic cylinders to push and pull the front and rear chassis frames apart. The working conditions here are drastically different, defined by extreme Radial Loads.

Why Spherical Plain Bearings dominate here When a heavy tractor sits in deep mud and attempts to steer, the crushing force on the pivot points is immense. A standard threaded Rod End can become a weak point here, as stress concentrates at the root of the threads. Consequently, on heavy-duty models, engineers typically specify Spherical Plain Bearings (SPBs) pressed directly into the cylinder eye or chassis hinge points. While this design is harder to install than a threaded rod end, it offers superior structural strength. When paired with optimized lubrication grooves, it prevents the bearing race from suffering plastic deformation (“pounding out”) under high-pressure, low-speed oscillation.

3. The Steering System (Front Axle)

On conventional front-axle tractors, Tie Rods and Drag Links are the safety-critical connection between the steering wheel and the tires. The core challenges here are Shock Loading and Contamination.

Combating the “Grinding Paste” Effect As the precision component closest to the ground, steering rod ends are constantly bombarded by mud and grit. If the seal fails, abrasive particles enter the housing, mixing with grease to form a typical “grinding paste” effect, accelerating wear on the ball and race.

In the field of bearing engineering, the destructive impact of contamination has been systematically studied. For instance, in the ISO 281 life modification model for rolling bearings, when the lubricant is contaminated with hard particles without effective isolation, the contamination factor ($e_c$) deteriorates significantly, potentially reducing actual fatigue life to less than 10% of the theoretical value [1].

Although rod ends belong to the sliding contact system and differ in failure mechanism from rolling bearings, the trend of damage caused by contaminants in heavy agricultural environments is highly consistent. Therefore, for external steering systems, a durable Rubber Boot and a maintenance strategy that includes regular Grease Flushing via Zerk fittings are mandatory, not optional.

[1] Reference: ISO 281:2007 Rolling bearings — Dynamic load ratings and rating life (Contamination factor discussion).

4. Cab Control Linkages

Moving inside the cab, the requirements for throttle, clutch, and hydraulic lever linkages shift 180 degrees. The goal is no longer brute strength, but Precision and Feel.

The Preference for Maintenance-Free Design Operators despise two things inside the cab: bringing a grease gun onto the upholstery, and “sticky” or inconsistent pedal feel. Therefore, the standard choice here is a Rod End with a PTFE (Teflon) liner. The PTFE liner provides a low, consistent coefficient of friction, eliminating metal-on-metal “stick-slip.” This ensures a smooth, linear response for the operator. Crucially, this maintenance-free design requires no lubrication for the life of the part, keeping the cab environment clean.

Quick Selection Guide

These four scenarios demonstrate that there is no “universal” rod end for agricultural machinery. Only by understanding the specific real-world conditions at each position can we make the correct engineering choice.

| Application Area | Key Stress | Key Challenge | Typical Choice | Maintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-Point Hitch (Top Link etc.) | Axial Tension/Compression | Needs high misalignment angle & length adjustment | Rod End (Threaded) - High-misalignment series | Regular Greasing |

| Articulated Steering | Extreme Radial Load | Preventing race deformation & thread breakage | Spherical Plain Bearing - Press-fit, no threaded shank | Central Lube / Heavy Grease |

| Front Steering (Tie Rod) | Shock + Mud Ingress | Contamination drastically reduces life (Industry consensus) | Rod End w/ Boot - Sealed & Reinforced | Flush-out Greasing |

| Cab Controls | High Frequency / Low Load | Requires smooth feel & no grease mess | PTFE Lined Rod End - Self-lubricating series | Maintenance Free |