When sourcing components for humanoid robots, the focus is often on AI, but the mechanical reality relies heavily on rod ends (also known as Heim joints). These critical mechanical linkages connect linear actuators to the frame, enabling fluid, human-like motion. However, standard industrial parts simply won’t cut it. For engineers and buyers, the market has converged on one specific solution that meets the strict demands of modern robotics: the liner type self-lubricating rod end.

Why Traditional Joints Are Obsolete for Humanoids?

If you have a background in heavy machinery, you are likely familiar with standard steel-on-steel rod end bearings equipped with grease zerks. For an excavator or a suspension bridge, these are fantastic. But for a humanoid robot? They are a liability.

- First, there is the maintenance issue. You simply cannot have a fleet of autonomous robots that need a technician to manually grease fifty joints every week. It’s a logistical nightmare.

- Second, cleanliness is paramount. Whether a robot is working in a sterile medical lab or a dusty warehouse, grease attracts contaminants and risks leaking.

This need for a “fit and forget” component has pushed the industry away from fluid lubrication and towards dry lubrication technology.

Liner Type Self-Lubricating Rod Ends are The Backbone of Robotic Motion

So, what is the answer? When we analyze the specs of top-tier robotic actuators, the industry has overwhelmingly standardized on the liner type. If you are looking at a spec sheet, you might see this described as a PTFE lined rod end or a composite liner bearing.

How It Works

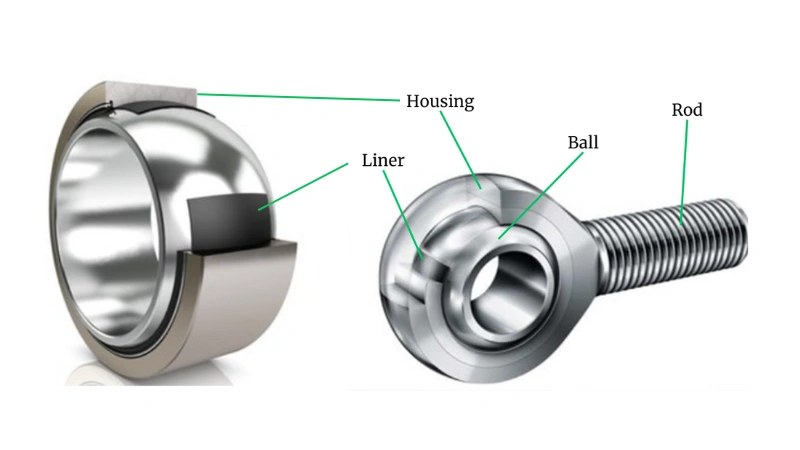

A spherical plain bearing of this type consists of an inner ring with a spherical convex outside surface (the ball) and an outer ring with a spherical concave inside surface (the housing). In a liner type, a specialized fabric or composite material—usually Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) woven with strengthening fibers—is bonded permanently to the inner surface of the housing. The ball then slides against this liner.

The picture below is a typical PTFE Lined self-lubricating spherical plain bearing and rod end:

This isn’t just a piece of plastic; it’s a tribological system. As the joint moves, the liner transfers a microscopic “solid transfer film” to the ball. This creates an incredibly slick, self-healing interface that actually gets smoother after the initial break-in period.

Why Liner Types Are the "Only" Choice

You might find suppliers pitching other “maintenance-free” options, but here is why the liner type is virtually the only rod end for humanoid robots that matters.

1. The Critical "Zero Backlash" Requirement

Humanoid robots are balancing acts—literally. They rely on complex feedback loops from IMUs and sensors to stay upright.

If you use a standard metal-on-metal joint, there is inherent clearance (space) between the ball and race to allow for oil. In robotics, we call this “slop” or backlash. Even a fraction of a millimeter of play in a hip joint translates to several centimeters of wobble at the head. This confuses the control algorithms and causes the robot to fall.

Liner type rod ends are typically manufactured with a “preload.” The liner is slightly compressed around the ball during assembly, eliminating internal clearance. This creates a true zero backlash rod end, ensuring that every micron of movement from the actuator translates directly into limb movement.

2. Mastering High-Frequency Oscillation

This is where many engineers get tripped up. Robots don’t just walk; they “dither.” To maintain balance, the servo motors make thousands of tiny, rapid micro-adjustments per second.

Under these conditions (small angle, high frequency), standard bearings suffer from fretting corrosion—where the lubricant gets squeezed out, and the metal vibrates itself to dust.

The PTFE liner acts as a damper. It absorbs these micro-vibrations and tolerates high-frequency oscillation without the risk of seizure. It provides a consistent, smooth feel that is essential for the “organic” movement we expect from humanoids.

3. Consistent Torque and "Stiction"

“Stiction” (static friction) is the force required to get the joint moving from a dead stop. High stiction causes jerky, robotic movements.

Because of the low friction coefficient of PTFE (one of the lowest of any solid material), liner type spherical bearings offer an incredibly smooth transition from static to dynamic motion. This allows for precise force control, which is vital when a robot is gripping a fragile object like an egg—or shaking a human hand.

Weight and Materials

Now that we agree that liner type is the way to go, what specific attributes should you look for when sourcing these motion control components?

The Shift to Lightweight Aluminum

In the industrial world, steel is king. In robotics, gravity is the enemy. Every gram of weight in a robot’s leg increases the moment of inertia, requiring larger motors and draining the battery faster.

Therefore, we are seeing a massive shift toward lightweight aluminum rod ends.

- The Body: High-strength 7075-T6 Aluminum alloy. It offers strength comparable to some steels but at a fraction of the weight.

- The Race: Often the liner is bonded directly to the aluminum housing, or a thin stainless steel insert is used for support.

- The Ball: Usually 440C Stainless Steel or Bearing Steel (Hard Chrome Plated) to ensure a hard, smooth surface for the liner to glide against.

High Misalignment Capability

Human joints rarely move in straight lines. A shoulder or hip joint needs to rotate and tilt simultaneously. Standard industrial rod ends often have a limited tilt angle.

For robotics, you should specifically request high misalignment rod ends. These feature a specialized neck and housing geometry that allows the ball to tilt significantly (sometimes up to 20-30 degrees) without the housing crashing into the stud. This maximizes the robot’s Degree of Freedom (DoF) and prevents catastrophic binding during complex maneuvers.

Why Other "Self-Lubricating" Types Fall Short

To be thorough, let’s briefly look at the alternatives so you know what to avoid.

- Sintered Bronze (Oil Impregnated): These are cheap and common in home appliances. However, they rely on oil stored in the pores of the metal. Under the heat and speed of a robotic limb, this oil can wick out or dry up. Once dry, they fail instantly. They simply lack the longevity required for a B2B commercial robot.

- Coated Types (DLC/MoS2): You might see “Diamond-Like Carbon” coatings marketed as high-tech. While excellent for aerospace engine parts, in a rod end application, coatings are incredibly thin. Once that thin layer wears through, you have metal-on-metal contact and rapid failure. A PTFE liner, by contrast, has depth and volume—it can wear gradually over millions of cycles while maintaining performance.

Conclusion

The robotics industry is moving fast, but the physics of articulation remains constant. While there are many types of joints in the catalog, the debate is effectively over for this specific application.

For the unique combination of zero maintenance, zero backlash, and lightweight performance, the liner type self-lubricating rod end is the definitive solution.

Whether you are designing the next warehouse humanoid or a research biped, the success of your motion control system depends on the quality of these connections. By choosing high-quality, PTFE-lined, aluminum rod ends, you ensure that your robot doesn’t just move—it performs.